Flowers for Algernon: Summary and Review

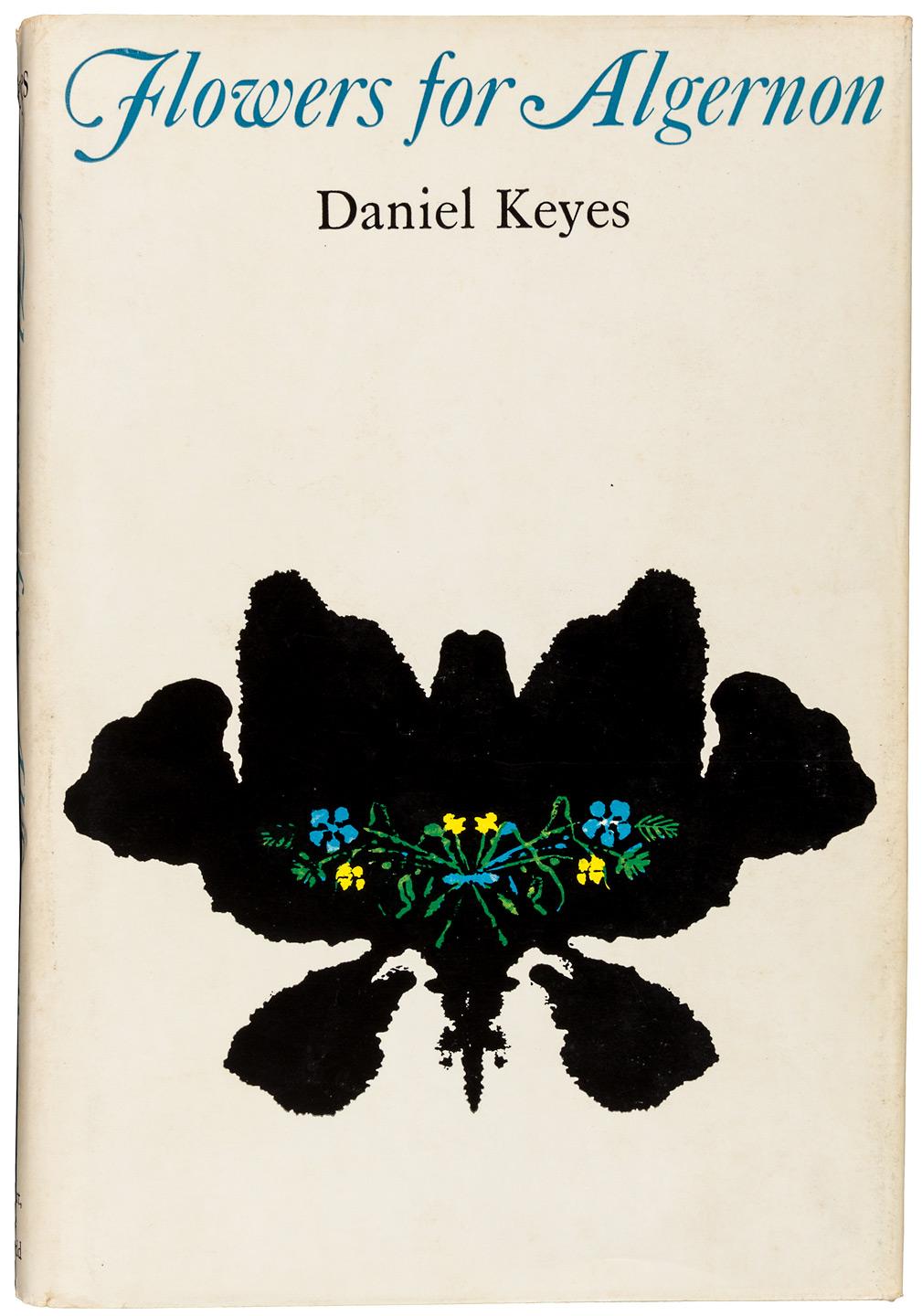

Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

Review

I went into this book completely blind and it blew my mind. I read the whole thing in one sitting. Flowers for Algernon had such a profound impact on me that I must have re-read this book more than 6 times—Daniel Keyes’ writing is so captivating that I can’t help but devour the whole book again every time I open it just a little bit.

I think the deepest impact this book had on me was the realization that we are all Charlie Gordon. You don’t have to get dementia or Alzheimer’s, but we will all decline cognitively in old age, whether from cell death or simply from deteriorating sleep quality that comes with aging.

We are also all Charlie Gordon behind the Rawlsian Veil of Ignorance. If intelligence is normally distributed, then the higher your IQ, the more likely it is the cosmic dice could have landed you on the lowest end of the bell curve instead.

This is due to balancing genetic polymorphism, where “The genes that increase risk of autism are disproportionately also genes that increase intelligence, and vice versa”, like how two copies of a mutation create sickle cell disease, but just one copy provides malaria protection.

Summary

The book follows Charlie Gordon, a man with an IQ of 68 who undergoes an intelligence-enhancing surgery and must learn to reckon with a life where his newfound intelligence alienates his friends and threatens his world.

Discussion and Notes

We read this book in Idea Club. What follows are both my own thoughts and my notes from that discussion.

Some themes covered by this book include:

- Happiness and socialization vs. Intelligence and loneliness

- Transhumanism, and the ethics of biological enhancement of humans

- How society treats those who have disabilities

I didn’t know this, but I found out later that there is an original abridged magazine edition that was later expanded into this book, an Audiobook adaptation, a 1968 movie adaptation, and a 2000 movie adaptation. It turns out that just as the text uses misspellings to convey Charlie’s changing mind, the audiobook production replicates this by using different voice acting techniques in the beginning vs. middle vs. end of the book.

Written in 1958, many parts of the book appear dated to the modern reader. Some examples:

- Using outdated psychology concepts like the Rorschach test, though even the author criticizes the Rorschach as useless.

- Charlie’s relationships with Alice and Fay follow the classic madonna-whore complex and the female characters don’t have more dimension outside of this.

- The fact that Charlie was easily able to get an apartment in New York, even overlooking Times Square, on a janitor’s salary.

- Outdated scientific ethics in 1958, like recording Charlie without him knowing, and two scientists winging their own research without any oversight or accountability.

The book highlights the disturbing part of the human condition that we don’t automatically extend empathy to everyone. Charlie has to become smart in order for us to value him (even in the reader’s eyes!), otherwise if he doesn’t have the interesting story of once having been smart, he would be completely forgettable to us.

Even today, we still have a limited understanding of what intelligence is exactly. There is the g factor theory, though I think my biggest criticism of it is that it explains too much. If “intelligence” is defined as “anything that makes you good at living”, then breaking it down as “verbal”, “quantitative”, “visuospatial”, “working memory”, etc. doesn’t help explain intelligence if at the end of the day anything good you do can be defined as “intelligence”, regardless of what it is that you do.

Industrial society used to value how much you know, but with supercomputers in our pockets, we now value how well you can relate to others. Medical school training is now shifting away from memorization, and towards empathizing with the patient.

Even during idea club meetings, we have this baggage from social indoctrination where we unconsciously want to show how smart we are. Even though it’s not required to read the book, we still feel like we have to perform intelligence by saying something smart. This is the industrial model of education as the source of imposter syndrome.

Resources: